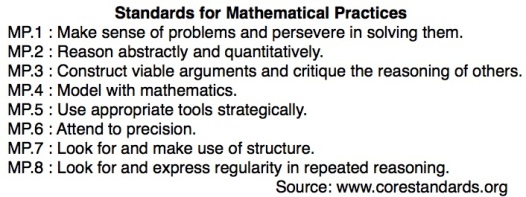

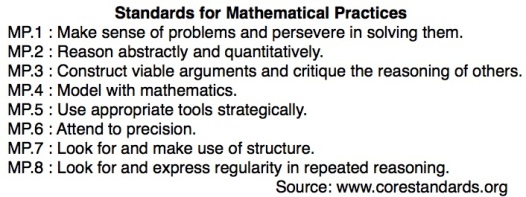

The Common Core’s Standards for Mathematical Practices are one of the, if not the most important standards teachers need to incorporate in their lessons. These standards are the epitome of problem solving. Our goal as math educators is not only for our students to understand the content, but to learn the life skill of problem solving and reason. We want our kids to be able to attack any type of problem (not just math) with confidence and a set of skills to guide them. The Standards for Mathematical Practices lay out this foundation for us.

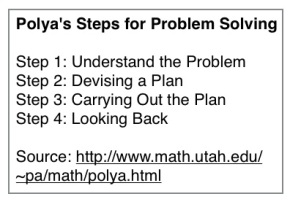

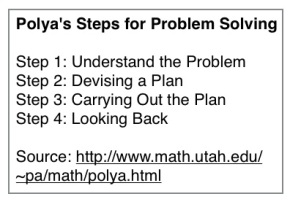

These standards share a similarity with George Polya’s Steps for  Problem Solving. Most math educators have heard and have used these steps, but they seemed to have been forgotten in recent years with the implementation of the common core. However, his work still lives on within these standards.

Problem Solving. Most math educators have heard and have used these steps, but they seemed to have been forgotten in recent years with the implementation of the common core. However, his work still lives on within these standards.

Each of the standards for mathematical practices are necessary for success in solving problems. The first standard, make sense of problems and persevere in solving them is vital to problem solving.This is a challenging standard for our students to demonstrate on their own. Some students are too quick to give up on a problem the moment they finish reading it. This first standard for mathematical practices encapsulates all of Polya’s four steps. Each of these steps aid students to understand and solve the problem. As educators we have to keep in mind that we cannot rush this process of understanding. Too often, due to time constraints and other outside factors, teachers move too quickly through problems without having their students really sink their teeth into a problem. Albert Einstein stated “If I had an hour to solve a problem, I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about solutions.” It is the understanding of the problem and coming up with a process to solve it is the most difficult. As teachers we need to be conscious of our pace and make sure that we are not moving along before our students understand the majority of the problem. For our students to reach this first mathematical standard, we need to be good models and slow it down, and demonstrate how to grapple with a problem. Polya’s first two steps are the longest, and that is because these steps are to understand the problem.

The second and third practice require students to analyze and defend their solutions. These standards focus on communicating the solution to a problem. We want students to question solutions and processes in our class. We want them to be able to reason abstractly and quantitatively and to construct arguments to prove their solutions. In order for our students to meet these important standards they need to communicate with each other. The most challenging part of this is for a student not to be afraid of asking a question. It is our job as educators to create and safe environment for students to ask questions. The only way our students can improve on these important skills is to make sure communication is happening in the classroom. It may be helpful to demonstrate a productive conversation or to point out good questions and good responses other students have made in class. These two standards really focus on proving their solution or other’s solution is viable. Standards two and three are directly related to Polya’s fourth step, looking back. In this step students need to make sure their answers make sense. To do this they must reason with themselves, and others, and construct an argument to why their solution is valid.

We can also make a connection between the second and first standards for mathematical practice. To understand the problem more deeply we must be able to have number sense, to reason abstractly and quantitatively. These are not just skills for math, they are skills for life. We want our students to be able to understand the difference between quantities given certain contexts. For example the difference between a 2% raise or a 5% raise, or the difference between one million dollars and one billion dollars.

The fourth standard is important and vital to Polya’s second and third step, developing and carrying out a plan. For a student to meet the fourth standard they must be able to model with mathematics, which includes drawing models or using manipulative. This standard cannot be reached if there is not enough exposure to using a model when solving a problem. When there is an opportunity for a student to use something physical to represent the problem, it will help with understanding the problem even more. Students should be exposed to manipulatives in math in the elementary grades, and when they reach the middle school level, they should be reminded they can model the problem by drawing or using a manipulative. A way to promote modeling with mathematics is intentionally including it in the lesson and having manipulatives easily available for students to use.

The fifth standard, use tools strategically, is a valuable skill our students need to learn. This involves knowing how to use all the math tools correctly and knowing when to use them. This not only is important in the math classroom, but it is an important life skill. This goes hand in hand with the previous standard in retrospect to Polya’s steps for problem solving.

Attending to precision is the sixth standard. We want our students to be accurate with their answers. In order to meet this standard, they must be able to meet the second standard, to reason abstractly and quantitatively. To be precise, students must realize their answer is reasonable. This is in Polya’s fourth step, to look back at the work and reason whether it is viable.

The last two standards are vital to problem solving. These both involve looking for structure and patterns to solve a problem. At the middle school level having students discovering regularity in repeated reasoning is prominent in solving problems. A way we can have our students meet this standard is to create discovery lessons, where students find patterns and repeated reasoning to solve similar problems. For example, having students discover exponent rules is a great way for them to recognize patterns in repeated reasoning to learn the rules. The important piece of these two standards is it is repeated reasoning. Students are supposed to make sense of the problem and reason with what they are doing to solve the problem. a further look into Polya’s work involve questions at each step, which is guiding the student through reasoning.

These standards need to be incorporated in the classroom as much as possible. As teachers we need to be conscious of including them in our lessons and take any opportunity to address them in the classroom. I have the standards hanging up in the classroom, and when it is relevant I will point out what standards that have been met. For example, if I hear students discussing and defending their solution with reasoning, I would address the class and explain how the conversation was a great example of the third mathematical practice. I also found it helped to list which practices students would be addressing in my lesson plan. In addition to having the practices on the wall, I have my students paste Polya’s four steps in the back of their notebook along with questions they should ask themselves for reference when they are stuck. It is a great tool for students to persevere through difficult problems.

These practices are not just for mathematical problem solving; they are life skills. Each practice is a skill used in everyday life, no matter what profession. This is why we teach mathematics. To have our students be prepared in the real-world. For our students to be able to reason and critique in social and academic situations. These standards can be applied to numerous real-world situations. The first and second practice alone are not just related to mathematics. They can be connected to different situations and different academia. In social sciences, people need to be able to listen, reason, critique, and argue different points.

It is unfortunate that teachers are being pressured for our students to only master the content. If we take a step back, our students can master the content through the skills we are teaching them. Not all problems on each topic will be the same. However, if we can get our students to recognize the content, and use the mathematical practices and Polya’s steps to solve the problem we as teachers are successful. Our job as math educators is not only to teach our students the content, but to develop these necessary skills so they can be successful in the future.

Problem Solving. Most math educators have heard and have used these steps, but they seemed to have been forgotten in recent years with the implementation of the common core. However, his work still lives on within these standards.

Problem Solving. Most math educators have heard and have used these steps, but they seemed to have been forgotten in recent years with the implementation of the common core. However, his work still lives on within these standards.